Claim Element Found in Prior Art Does Not Support Nexus Between Claimed Invention and Commercial Success

In Yita LLC v. MacNeil IP LLC,[1] the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit recently reminded patent owners and applicants that in order for commercial success of an invention to support non-obviousness, the required nexus between the claimed invention and its commercial success cannot rest solely on a claim element that is known in the prior art.

MacNeil owns patents directed to a “vehicle floor tray . . . thermoformed from a polymer sheet of substantially uniform thickness.” One of the claimed features of the invention is a specified close conformance of the vehicle floor tray to a vehicle foot well. MacNeil’s patents are embodied in the popular WeatherTech® brand of automobile floor trays.

Yita filed petitions for inter partes review (IPR) challenging MacNeil’s patents on grounds of obviousness under 35 U.S.C. § 103. As the patent statute says, “a patent for a claimed invention may not be obtained . . . if the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious before the effective filing date of the claimed invention to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains.” Obviousness is a question of law based on underlying facts. Such facts, known as the Graham factors, include the scope and content of the prior art, differences between the prior art and the claims, the level of ordinary skill, and relevant evidence of secondary considerations. Secondary considerations (i.e., objective indicia of non-obviousness) may include evidence of criticality, commercial success, long-felt but unsolved need, industry praise, failure of others, unexpected results, and skepticism of experts.

When a patent owner (or applicant) asserts that commercial success supports non-obviousness, the proponent must establish that there is a nexus, that is, a legally and factually sufficient connection, between the claimed invention and the commercial success of that invention.

In one of the IPRs, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB or Board) reviewed Yita’s asserted prior art in support of its obviousness challenge and found that each element of the challenged claims was disclosed in three references. The Board further determined that a relevant artisan would have been motivated to combine the teachings of the three prior art references with a reasonable expectation of success to arrive at the claims of the MacNeil patent.

As it was required to do, the Board then considered MacNeil’s evidence of secondary considerations. The Board properly recognized that for MacNeil’s evidence of secondary considerations to be given substantial weight in the determination of obviousness or non-obviousness, there needed to be evidence of the required nexus. However, when the patent owner demonstrates that the marketed invention is coextensive with the claims, the patent owner is entitled to a presumption of nexus. That is what the Board found and, accordingly, evidence of secondary considerations, namely, commercial success of the claimed invention, was determined to be relevant and was given substantial weight in the obviousness analysis.

In its final written decision, the PTAB determined that all of the evidence taken together was persuasive in MacNeil’s favor. More specifically, the Board found the evidence of commercial success to be “compelling” due to the claimed feature of close conformance of the vehicle floor tray to a vehicle foot well not being well known. The Board had, however, already found that this feature was disclosed in the prior art asserted by Yita.

Yita appealed the final written decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC). The CAFC reversed the PTAB’s decision based on two legal errors committed by the Board.

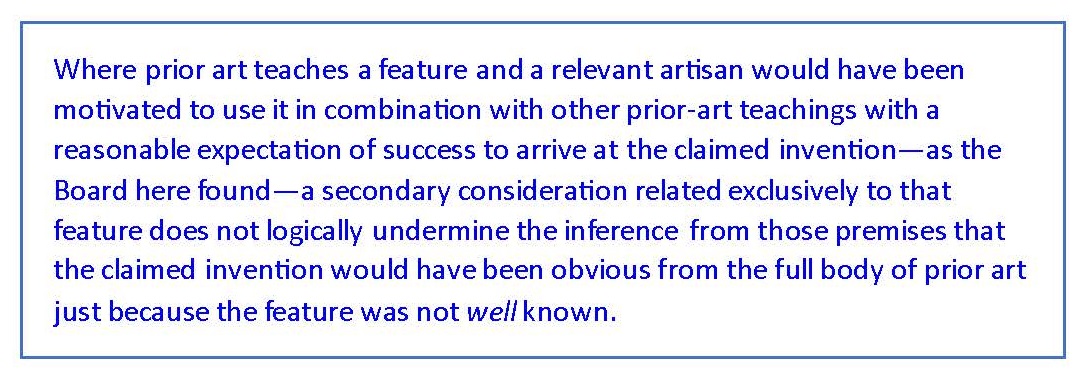

First, the CAFC explained that the Board failed to recognize that when a claim element is found in the prior art, that same claim element cannot be the basis for a finding of nexus when examining commercial success evidence. The Court noted that case law is clear that a feature exclusively related to the nexus (i.e., the close conformance feature) need not be “well known” but only known in order to be discounted in the analysis. Because the Board had already found that the feature of close conformance was known in the prior art, it could not find that MacNeil had proven a nexus or credit the evidence of commercial success on the basis of that same feature. The CAFC succinctly summarized the issue:

The Court also pointed out that while determining whether to afford a presumption of nexus involves only a comparison of the commercialized product to the claims, the final determination of nexus further requires comparison of the claims and the reasons for commercial success to the prior art. That MacNeil was entitled to a presumption of nexus did not mean that such nexus was ultimately proven.

The second error committed by the Board was its misapprehension of whether nexus could relate to a single claim element or the claimed combination as a whole. Prior CAFC precedent says either, but the Board incorrectly determined that it was only the latter. Based on this misunderstanding of law as well, the Board erroneously discounted its own finding that the close conformance feature was disclosed in the prior art – the very feature exclusively relied upon by MacNeil to demonstrate commercial success of its claimed invention.

After correcting the PTAB’s errors, and thus determining that MacNeil had not established commercial success of its patented invention under existing precedent, the CAFC held that there was no evidence to counter the Board’s initial findings that all claim elements were found in the prior art and that the ordinarily skilled artisan would have been motivated to combine them to arrive at the claims of the patent challenged by Yita. Thus, the CAFC reversed the Board’s final written decision and found that Yita had successfully challenged the claims as being unpatentable for obviousness.

Proving secondary considerations, i.e., objective indicia of non-obviousness, is difficult and proving commercial success is especially so. Practitioners must always make sure that all legal requirements are satisfied, and that there are no facts that would disqualify any evidence as being irrelevant to the inquiry.